Lu Moo, better known as Granny Lum Loy and also known as Lee Toy Kim, had an unlikely, atypical and very long active life. Born in Taishan (Toishan or Hoisan) in southern coastal China in the mid 1880s, she was brought to the Northern Territory in 1894 as an adopted daughter of a family with a business in Darwin’s Chinatown. From 1918, with a short absence due to evacuation during World War 2, she managed a market garden, mango orchard and poultry business, selling her produce locally and shipping mangos to Western Australia.

Granny Lum Loy was a well-known Darwin personality and her funeral in 1980 is described as ‘one of the biggest and longest in Darwin’s history’. In 2001, Lum Loy Lane was declared the Australian Capital Territory suburb of Gungahlin, commemorating her contribution to primary industry. She is also featured in the ‘Entrepreneur’ section of the National Museum of Australia’s Harvest of Endurance Scroll, a 50-metre-long scroll that represents two centuries of Chinese engagement with Australia.

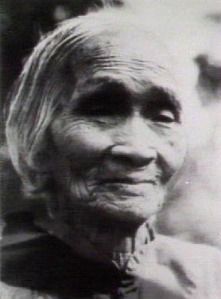

Lu Moo or ‘Granny Lum Loy’ Courtesy Northern Territory Library.

Ted Egan, songwriter and NT Administrator (2003-2007), remembered her as a ‘wonderful old Chinese lady’ and, he said, ‘she was much loved. She used to walk into town every day with two baskets she used to sell’.

Chinese women in Darwin

When Lu Moo arrived in Palmerston (Darwin) in 1894 it was a small town (non-Indigenous population less than 5000 in 1901). Chinese male indentured servants began arriving in Palmerston in 1874. The Chinese outnumbered Europeans at the turn of the century, their numbers peaking at 3658 in the 1891 census. Palmerston had a substantial Chinatown and businesses, especially along Cavenaugh Street were thriving concerns in the late nineteenth century.

Chinese men greatly outnumbered Chinese women in Australia at the turn of the century, with fewer than 500 Chinese women in the whole of Australia by 1901. Darwin was no exception – very few non-Indigenous women lived in Darwin at the time of the 1891 census.

In the last decades of the nineteenth century leading up to Federation white Australians displayed extreme prejudice against the Chinese and highly emotional debates took place on excluding Chinese migrants. The Immigration Restriction Act was one of the first acts passed by the new federal government in 1901 and was specifically aimed at preventing Chinese migration and forcing those already living in Australia to return to China.

One of the arguments against Chinese migration focused on the extreme gender imbalance. Australians had worried about gender imbalance within the British population throughout the colonial period. Similar fears were raised about the Chinese gender imbalance:

Chinese men also expressed unwillingness to bring their womenfolk to the antipodean colonies. They found Australia and its European residents barbaric and did not want to subject their mothers, wives and daughters to the physical hardships and social indignities that the men experienced. Furthermore, a Chinese man could more easily fulfill his duties to the elders in his family if his wife stayed in China to look after them.

For whatever reasons, Lu Moo and another girl, residents of Taishan were adopted in 1892 by Fong Sui Wing, a prominent Chinese business family and brought to Darwin’s thriving Chinatown. Lu Moo worked in her adopted family’s shop until her marriage in 1901.

Mrs Lum Loy’s garden

Lu Moo married Lum Loy, a mining engineer and, around 1901 moved with him to the wolfram mines near Pine Creek and then to Brock’s Creek a thriving mining centre. Lum Loy died in 1918 and Mrs Lum Loy returned to Darwin with her daughter, Lin (‘Lizzie’) Yook Lin, and launched her agricultural enterprise.

[S]he rented land and single-handedly planted a mango orchard of 200 trees, carrying water from the well and compost from a large pit. It was a prolific enterprise that she harvested herself, sending the fruit to Western Australia.

Her first market garden was on land near the Darwin Bowling Club. She subsequently ran a market garden and poultry run in Stuart Park. According to the Northern Territory Library’s brief biography:

Every day she would walk from Stuart Park to town to sell her produce and pray at the Joss House. She always wore traditional black trousers and broad brimmed hat, carrying her vegetables and eggs in baskets slung from a yoke over her shoulders.

During World War 2, Granny Lum Loy and her daughter were evacuated to Alice Springs where they ran a fruit shop. Her daughter died in Alice and her mother returned to Darwin and established a market garden which she operated until 1974. The indomitable 80-year-old Granny re-established her garden after the destruction of Cyclone Tracey and continued her business until her death in 1980.

A remarkable woman

By any standards Mrs Lum Loy’s enterprise was pioneering. Many women have demonstrated their intelligence and expertise stepping in to run a business started by their menfolk if the men die. But Mrs Lum Loy started her own new business in a completely different area from that of her mining engineer husband.

We can only speculate that Mrs Lum Loy may have been an active gardener in the mining camps where she and her husband spent more than 15 years, perhaps feeding both her own family and miners, the latter perhaps as a business enterprise.

She must have had considerable drive and agricultural expertise required to establish a large-scale mango orchard in Darwin. And, given the ongoing gender imbalance in the Northern Territory, that she chose and was able to maintain herself as an independent woman for some 60 years after her husband’s death is remarkable.

Granny Lum Loy’s market garden contributed to the diets of generations of Darwin residents.

Further reading

Barbara James, No Man’s Land: Women of the Northern Territory, Collins, 1989 – Barbara James has written the most comprehensive account of Granny Lum Loy’s life, based on an interview with her shortly before her death. Her book also is a comprehensive history of women’s contributions to and lives in the Northern Territory.

Kate Bagnall, Golden Shadows on a White Land, PhD thesis, University of Sydney, 2006 online at

http://ses.library.usyd.edu.au/bitstream/2123/1412/1/01front.pdf

Clive Moore, ‘A precious few: Melanesian and Asian women in northern Australia’, in Gender Relations in Australia: Domination and Negotiation, Kay Saunders and Raymond Evans (eds), Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, 1992, pp59-81.

A short biography of Granny Lum Loy is available on the Northern Territory website,

www.ntl.nt.gov.au/about_us/publications/territory_characters#GrannyLumLoy

The ACT Government’s official declaration of Lum Loy Lane: Public Placenames 2003 No 11, ACT Government,

www.legislation.act.gov.au/di/2003-331/current/pdf/2003-331.pdf

The Chinese-Australian Historical Images in Australia website has images and biographies of Granny Lum Loy’s adopted father, Fong Sui Wing,chia.chinesemuseum.com.au/biogs/CH00950b.htm, and an image of Fong Sui Wing is on the Northern Territory Library website, www.territorystories.nt.gov.au/handle/10070/33501

The Harvest of Endurance Scroll is online, National Museum of Australia website,

www.nma.gov.au/collections/collection_interactives/harvest_of_endurance_html_version/explore_the_scroll/entrepreneurs/

Short biographies of Lum Loy and images of Chinese in Australia are available on thehttp://www.chia.chinesemuseum.com.au/biogs/CH00948b.htm

The Australian Government Culture Portal includes an article with useful background, ‘Chinatowns Across Australia’,

www.cultureandrecreation.gov.au/articles/identity/chinatowns/

The National Library’s Picture Australia, Chinese-Australian heritage trail,www.pictureaustralia.org/trail/chinese-australian+heritage

The Northern Territory Library website has a number of images of Chinese market gardens:

Peel’s Well garden, 1878-1883

www.territorystories.nt.gov.au/handle/10070/15356

Pine Creek Chinese market gardens, c1910-1914

www.territorystories.nt.gov.au/handle/10070/14609

Rice gardens near Darwin, 1891

www.territorystories.nt.gov.au/handle/10070/13737